Autoantibodies in Scleroderma Patients Trigger Profibrotic and Proinflammatory Responses, Study Finds

Autoreactive antibodies, or autoantibodies, were detected in the blood of patients with scleroderma (also called systemic sclerosis, or SSc) and shown to trigger proinflammatory and pro-scarring responses when added to skin fibroblasts from healthy subjects, researchers report.

Their study, “Immune complexes containing scleroderma-specific autoantibodies induce a profibrotic and proinflammatory phenotype in skin fibroblasts,” was published in the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy.

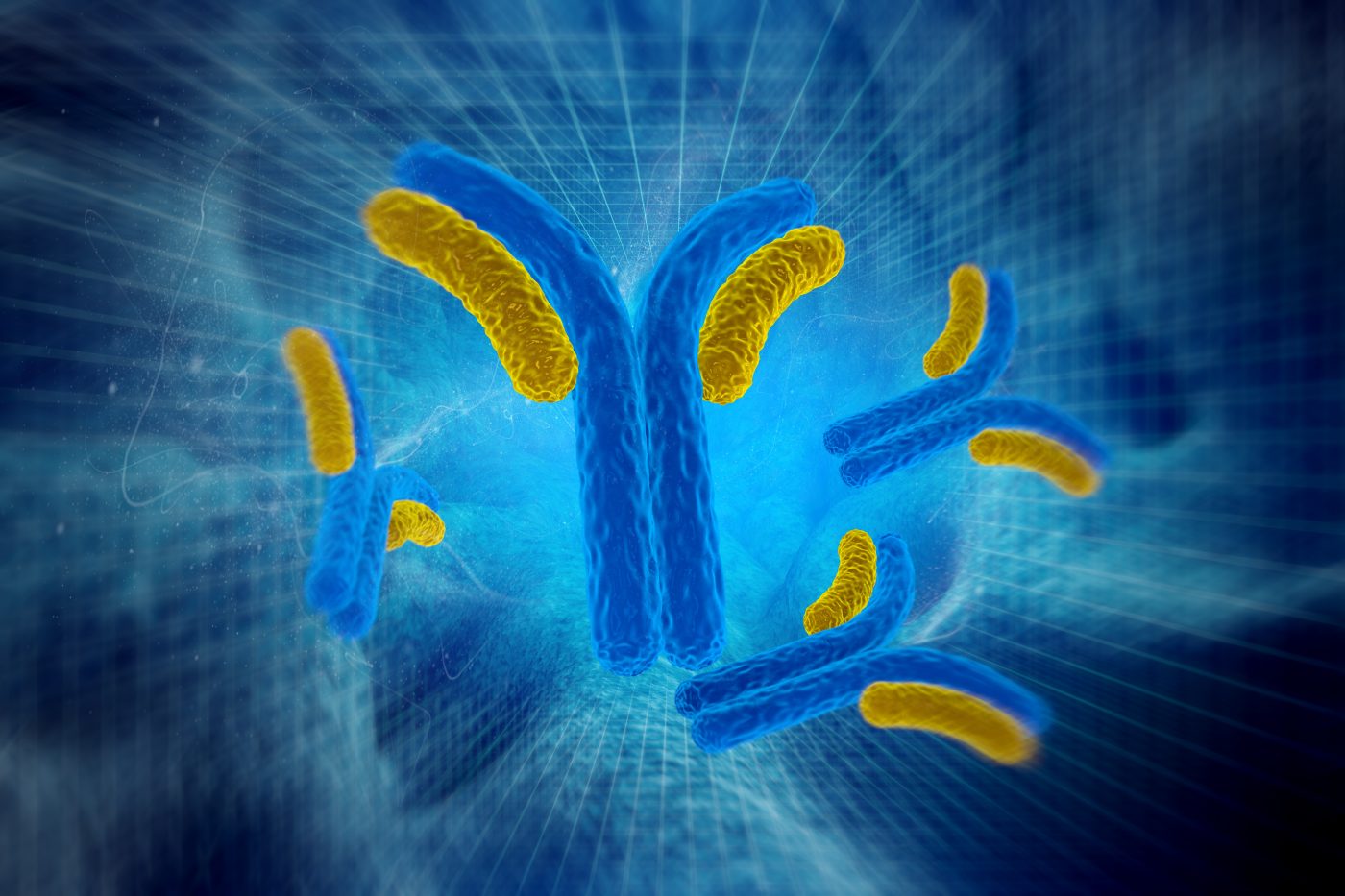

A hallmark of SSc is the production of autoantibodies, including those that target nucleic acids or DNA/RNA-binding proteins. These are detected in more than 95% of patients at diagnosis. The binding of antibodies to their target protein is called immune complexes.

But the role of immune complexes in systemic sclerosis requires further investigation, especially their potential to cause inflammation and scarring (fibrosis).

Researchers used skin fibroblasts — the major cells responsible for the production of collagen and fibrosis — from eight healthy subjects and from two patients with diffuse cutaneous SSc.

They purified immune complexes from blood samples of 16 SSc patients — seven with diffuse cutaneous SSc and the remaining with limited cutaneous involvement — and of three types of subjects used as controls: eight healthy subjects, two patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and two patients with primary anti-phospholipid syndrome (APS).

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the production of autoantibodies, those that attack the body’s own tissue. APS, also known as Hughes syndrome, is a disorder of the immune system that causes an increased risk of blood clots.

Researchers added the immune complexes from each condition to healthy fibroblasts, and after an incubation period of 24 or 48 hours they measured several markers of inflammation.

First, they confirmed that the blood samples from the SSc patients had a much higher load of immune complexes compared to those from the healthy controls. Moreover, they confirmed that these immune complexes contained scleroderma-specific autoantibodies.

The results showed that the SSc-immune complexes affected the function of healthy skin fibroblasts.

Specifically, adding SSc-immune complexes to the cells triggered the production of molecules involved in key processes in the progression of SSc — vascular dysfunction, promoted by the release of endothelin-1 (a potent vasoconstrictor) and interleukin (IL)-8; inflammation, as shown by an increase in proinflammatory markers such as ICAM-1, IL-6, interferons, and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1); and fibrosis, shown by an increase in the secretion of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) and pro-collagen Iα1.

No increase in these markers was detected when fibroblasts were incubated with immune complexes from healthy subjects.

Also, researchers saw that the immune complexes from both SLE and PAPS samples had no effect in modulating the expression of fibrotic molecules, such as pro-collagen Iα1.

The results also suggest that the proinflmamtory and profibrotic effects of SSc-immune complexes might be mediated via a group of immune sensors called Toll-like receptors, or TLRs.

Overall, “using skin fibroblasts from [normal healthy subjects] as an in vitro model, we observed that SSc-ICs [SSc-immune complexes] can trigger proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators,” researchers wrote.

“Our data suggest that SSc-ICs might be a novel player in the [disease development] of scleroderma, fitting well with the diagnostic and prognostic role of SSc-specific autoantibodies,” the team concluded.