Autoantibodies Against Telomeres May Help Identify SSc With Lung Disease

Written by |

Autoantibodies against proteins of the telomeres — the protective caps of chromosomes and a marker of lifespan — were found in scleroderma patients with lung disease and shorter telomeres, a new study reveals.

The findings suggest these autoantibodies could serve as a novel biomarker for scleroderma with lung disease.

The study, “Autoantibodies targeting telomere-associated proteins in systemic sclerosis,” was published in the journal Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases.

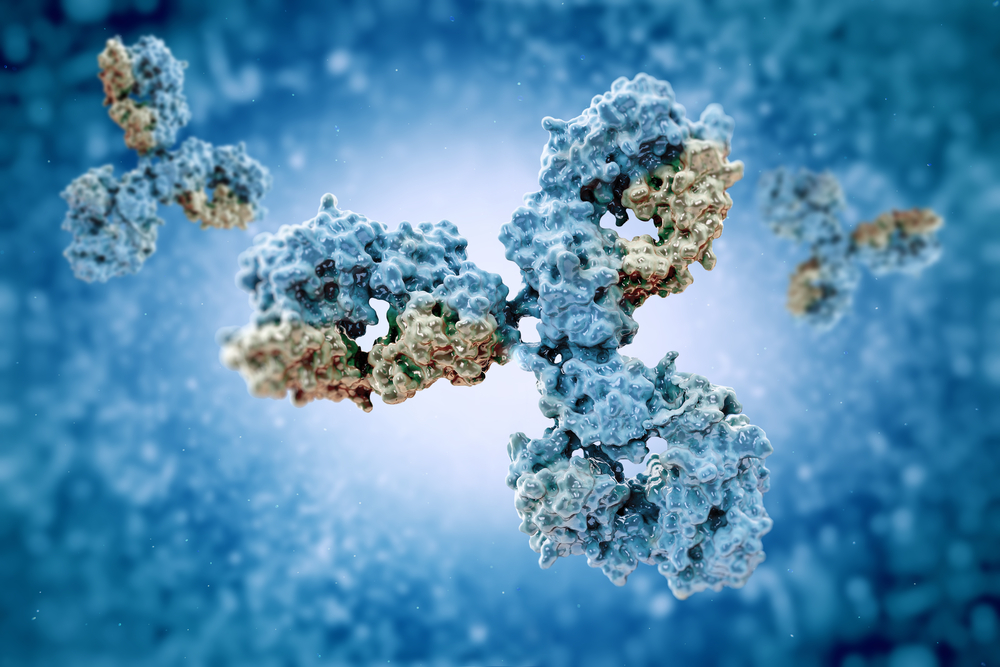

Telomeres are coverings on the tips of chromosomes that, as cells age, become shorter and work as a kind of “molecular clock.”

Previous studies have reported that people with scleroderma, or systemic sclerosis (SSc), who have shorter telomeres in white blood cells (lymphocytes) are at higher risk for interstitial lung disease (ILD). ILD is an umbrella term for a group of lung disorders characterized by inflammation and scarring (fibrosis) of the lungs. It is a frequent complication of scleroderma.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California, and the University of California in San Francisco (UCSF), tested whether scleroderma patients with shorter telomeres carry autoantibodies against the telomerase and shelterin proteins of telomeres.

Two groups of patients, one from Johns Hopkins and the other from UCSF Scleroderma Centers, were included in the study.

To test for autoantibodies against telomerase, the researchers analyzed blood samples from 200 patients of the Johns Hopkins group, and 30 healthy individuals who served as controls.

The analysis revealed that six patients (3%) were positive for these autoantibodies, while all the controls were negative. In addition, seven patients had autoantibodies against telomerase or one of the six shelterin proteins. Again, no autoantibodies were found in the healthy individuals.

TERF1 was the most commonly targeted shelterin, with 22 patients (11%) testing positive for such autoantibodies. In the UCSF group, 18 of 242 patients (7.4%) also had autoantibodies against TERF1.

Combining the two groups, a total of 40 patients (9%) tested positive for anti-TERF1 antibodies, in contrast to only 1.3% in 78 controls.

To assess whether anti-TERF1 autoantibodies were exclusive of scleroderma, they measured their levels in 60 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and 60 with myositis (inflammation of the muscles).

The analysis showed that only one patient with rheumatoid arthritis and one with myositis (1.7% each) were positive for anti-TERF1 autoantibodies, a rate similar to that seen in healthy individuals.

To assess whether the presence of the autoantibodies were linked with shorter telomeres, the researchers then measured the telomeres’ length in white blood cells from the UCSF group.

Results showed that compared to patients without autoantibodies, the telomeres were shorter than expected for their age range in significantly more patients with anti-TERF1 autoantibodies — 78% vs. 43%.

Another method for quantifying telomere length (Flow-FISH), which is more accurate and sensitive, according to the researchers, confirmed the link between anti-TERF1 autoantibodies and shorter telomeres.

Patients with anti-TERF1 autoantibodies were generally younger than those negative for these antibodies (mean age 52.6 vs. 56.4). The presence of autoantibodies was linked with a history of severe lung disease and worse lung function, as shown by the lower percent predicted diffusion capacity (DLCO), 58.0 vs. 67.9. DLCO measures how much oxygen is transferred from the lungs into the bloodstream.

Also, anti-TERF1 autoantibodies were associated with a greater risk for severe muscle disease (three times higher) and inflammatory arthritis (about two times higher).

Finally, the researchers screened 152 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), an inflammatory lung disease also linked with shorter telomeres, for anti-TERF1 autoantibodies. They found that 11 patients were positive (7.2%), which suggests that telomere-targeting antibodies might underlie lung disease.

“We describe a novel subgroup of patients with SSc and IPF with autoantibodies targeting the telomerase/shelterin complex that in SSc is associated with short telomeres in peripheral lymphocytes and the presence of lung disease,” the researchers wrote.

“These autoantibodies could serve as novel biomarkers for systemic sclerosis and specifically for systemic sclerosis lung disease,” they concluded.