Therapeutic Plasma Exchange and Scleroderma: An Exclusive Interview with Edward Harris

Edward Harris, the man behind the Scleroderma Education Project, recently presented a review and analysis of published data about therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), a potential technique for treating scleroderma, at the American Society for Apheresis (ASFA) 2016 Annual Meeting. The presentation, “Therapeutic Plasma Exchange for the Treatment of Systemic Scleroderma: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis,” and the study concluded that TPE may be a safe option for controlling or even reversing scleroderma progression.

In 2015, Harris and colleagues published a case report of a man with CREST syndrome successfully treated with TPE for 21 years. Harris’ long-term interest in scleroderma stems from the fact that he — originally the founder and CEO of a software company — is the scleroderma patient in the case report, and his efforts to understand his disease has benefited thousands of patients since he first published the Scleroderma FAQ in 1995.

The Scleroderma Education Project reflects Harris’ eagerness to improve both patient and physician knowledge about the disease.

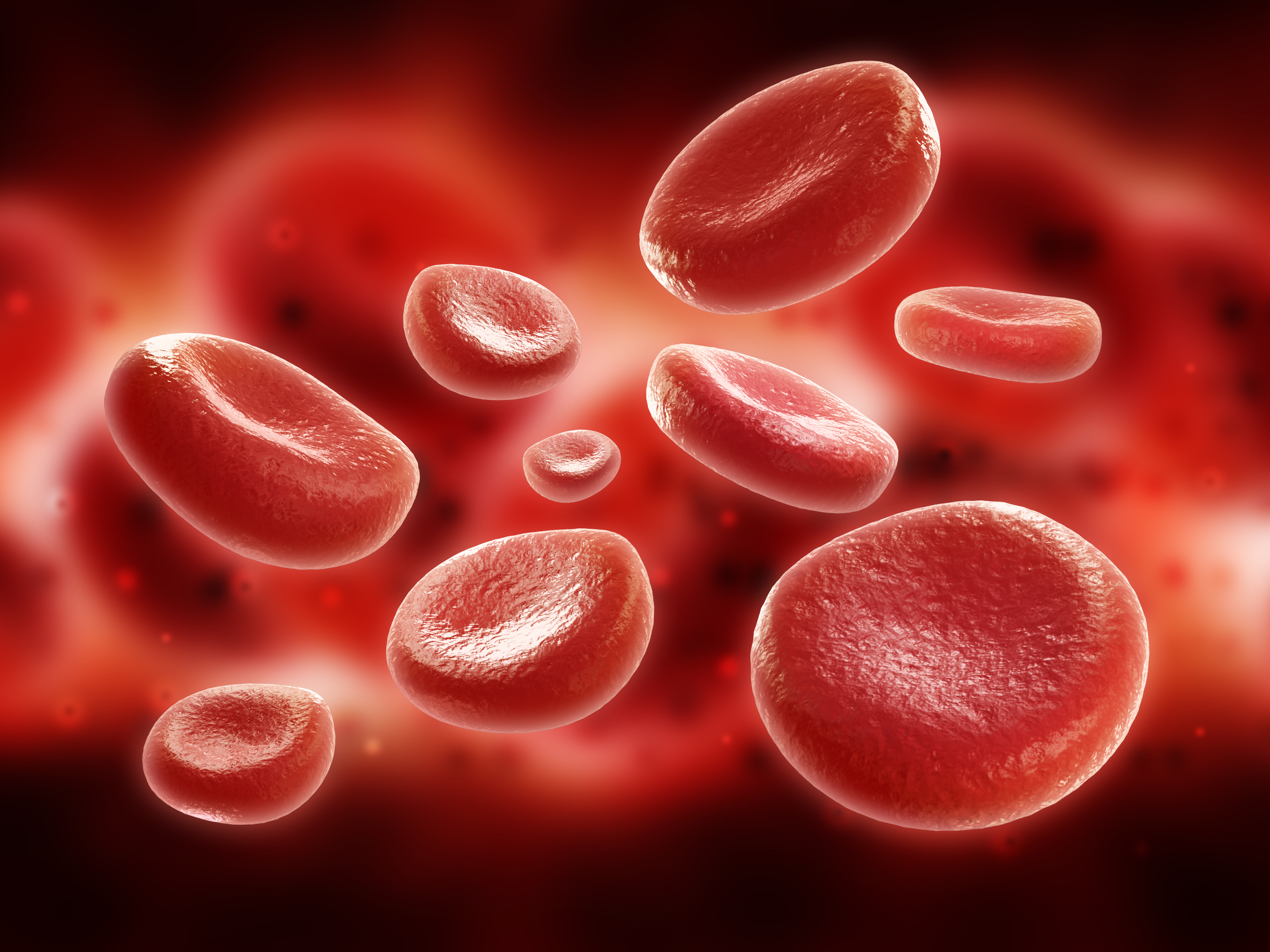

Harris first suggested a new reason for the underlying cause of scleroderma in 1993, a hypothesis resting on observations that scleroderma patients have abnormally thick blood. Research has shown that this is because red blood cells become stuck to each other, forming aggregates that obstruct blood flow and block the smallest blood vessels, called capillaries. These blockages lead to disease symptoms.

Early research suggesting such mechanisms came from a group in the Netherlands that used TPE for treating Raynaud’s symptoms in scleroderma patients. A common interpretation of the effectivity of TPE in scleroderma is that the treatment removes potentially harmful circulating antibodies from the blood, but Harris is convinced that the explanation lies in the properties of red blood cells themselves.

In the review presented at the ASFA meeting, Harris reported on 40 publications, with a total of 533 patients, covering the use of TPE in scleroderma. The review found that many of the articles were of poor quality, and missing information necessary to evaluate the results. Only nine articles met the top grading criteria, and another 15 provided useful data despite flaws.

The studies showed that TPE treatment improved blood viscosity, and particularly digital ulcers and Raynaud’s symptoms. TPE was also shown effective for other disease symptoms.

The review found the treatment to be safe, with a 3 percent rate of side effects, all mild. It also calculated an annual cost for TPE treatment, showing that, while expensive, it was on par with standard pharmacological options used to treat autoimmune diseases.

Harris shared his thoughts about the review and TPE treatment in an interview with Scleroderma News, provided below in a Q&A format:

Q: Could you briefly explain what is the basic concept behind TPE, and how it is performed?

Harris: Therapeutic plasma Exchange (TPE) is a procedure where a large volume of blood is extracted in a continuous flow process. The main blood components (red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets) are separated from the plasma by a centrifugal process, and the extracted cells are re-combined with a plasma replacement such as sterilized albumin. The normal reason for using TPE is to remove potentially harmful circulating factors such as antibodies from the plasma. A one blood volume plasma exchange removes about 66% of blood circulating factors.

The procedure is normally performed in an outpatient setting and is typically done using two venous catheters, usually one in each arm. It takes about one and one half to three hours, depending on the volume being exchanged and blood flow rates.

Q: You have conducted a comprehensive literature review on TPE as a treatment option for scleroderma. The data showed that TPE led to a significant improvement in disease symptoms. Could you elaborate on which ones, and on the extent of the improvements?

Harris: One of the most striking and common findings reported in many of the studies reviewed for this article was that, for the majority of patients, Raynaud’s symptoms usually disappeared completely or were significantly reduced, and long-standing digital ulcers started healing after three to four TPE treatments. This was mentioned in 13 of the 40 reviewed articles. In one study, even though only a single round of four weekly TPE treatments was done, the elimination of Raynaud’s symptoms lasted for six to nine months and in some cases longer, and no patients had return of digital ulcers within the three-year follow-up period. With longer treatment periods, there is also improvement in other symptoms, such as tendon friction rubs and Modified Rodnan skin scores.

One recent case report followed a patient diagnosed with CREST syndrome in early 1990, who began regular TPE treatments (16 treatments per year) in late 1993 as the sole systemic intervention. The patient went into remission after about two to three years of TPE treatments, including a major reduction of Raynaud’s symptoms, complete elimination of GERD [gastroesophageal reflux disease], and reversal of early lung damage. He has remained in remission to the present day. While this needs to be replicated in a full clinical trial, it suggests that long-term regular TPE treatments may be an effective way of treating patients with limited scleroderma and potentially other variants of scleroderma as well.

Q: TPE treatment has been shown, in general, to be well-tolerated. What were the main adverse effects reported by patients, if any?

Harris: The safety profile for long-term use of TPE is excellent. The most common side effects are very short-term, e.g., hypotension or fatigue for a few hours following a treatment.

Cid et al. (2014) reviewed the efficacy and safety of TPE in 317 patients and 2,730 procedures over an 11-year period. Observed adverse events occurred in just 3% of the procedures, and in all cases the adverse events were mild and patients were able to complete the scheduled TPE treatment.

Q: In your opinion, what are the main advantages or clinical benefits that TPE offers to scleroderma patients when compared to other therapies.

Harris: The preponderance of evidence suggests that long-term TPE may offer a low-risk way to control and in some cases reverse scleroderma symptoms. In contrast to current immunosuppressive treatments that carry significant risk, long-term TPE appears to be safe, well-tolerated, and with very few, mostly minor side effects. While TPE is a fairly expensive procedure, annual costs are in line with modern pharmaceuticals commonly used to treat scleroderma and other autoimmune diseases.

Q: Given your experience with the disease, both at a personal level and as a researcher, what would you advise to a scleroderma patient interested in trying TPE treatment?

Harris: One of the challenges that any patient will face who is interested in trying TPE treatments is the lack of knowledge among scleroderma clinicians and researchers that TPE treatments have been demonstrated to be a beneficial treatment for scleroderma patients in about 40 published articles. Currently, TPE treatments for treating scleroderma are classified as a Category 3 intervention by the American Society for Apheresis. This category indicates that in the opinion of the Guidelines committee, the research is equivocal and physicians should make an individual determination on the suitability of using TPE based on the patient’s situation. As a result, getting insurance coverage can be challenging, although current Medicare guidelines covers TPE treatments for scleroderma in many cases, and many insurance companies follow Medicare guidelines in making coverage decisions.

My current thought is that TPE is likely to be an effective treatment for patients with limited scleroderma, but it may not be as effective (at least at the same treatment frequency) for patients with diffuse variants of scleroderma. Patients also need to understand that TPE treatments, like any other current treatment option, with the possible exception of hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCT), need to be continued on a permanent basis to maintain any resulting symptom improvements, just as patients with diabetes need to stay on insulin and patients with HIV need to stay on antiretroviral drugs. Patients will also need to have physicians who are open to learning about the research on using TPE to treat scleroderma, and who are willing to “go to bat” for them with insurance companies.