Scleroderma Education Project, Delves into Organ Involvement in Recent Post

Written by |

In July 2014, Edward Harris launched a website called the Scleroderma Education Project, where he writes and publishes articles providing comprehensive, unbiased, and research-based information about scleroderma. His articles are crafted to an audiences’ varied concerns — including a March 8 post on organ involvement in the disease — and his Education Project is now a trusted source of information about scleroderma, recording visits from more than 12,500 patients in 115 countries in the past six months alone.

The Scleroderma Project rests on three pillars. Its primary focus is Education, and while most of the articles and blogs on the website are written for people with the disease, some aim to educate physicians.

Patient Support is its second focus, and is based on Harris’ conviction that patients, to most effectively work with their team of doctors, need to well understand their disease. The project supports patients through its posts, and through online forums and direct communication via email and, occasionally, telephone.

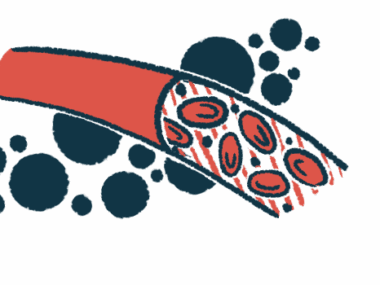

Research is the final focus. Harris, who holds master’s degrees in research clinical psychology and computer science from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, developed a new disease model for scleroderma pathogenesis based on research showing that most patients have blood hyperviscosity. He was also involved in the development of a successful treatment approach that was able to reverse scleroderma disease symptoms. The technique is called therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), and Scleroderma News previously published an article based on it.

Another, less official, focus is simply monitoring the various scleroderma patient forums found online and responding to them with website articles and blogs. The recent article,“Yes, You DO Have Internal Organ Involvement, But…,” in fact, came directly from a social media group poster’s question concerning organ involvement in disease pathogenesis.

Scleroderma, also referred to as systemic sclerosis, is an autoimmune connective tissue disease. It is characterized by thickening of the skin, caused by excessive accumulation of collagen, and by injuries to small arteries. There are two overlapping forms of scleroderma — limited cutaneous scleroderma, affecting the skin on the face, hands and feet, and diffuse cutaneous scleroderma, which covers more of the skin, and is at risk of progressing to the visceral organs, including the kidneys, heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract.

According to Harris, the real key to understanding disease pathogenesis and organ involvement lies in the word “systemic,” which is part of both “limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis” and “diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis”.

“If you develop one of the systemic variants of scleroderma, you DO have internal organ involvement. That is what is meant by ‘systemic,’” Harris wrote in the article. “Often this involvement is only microscopic (seen when tissue is examined under a microscope) but not symptomatic. Systemic scleroderma is often, but not always, a steadily progressive disease.”

Progression depends on the individual patient, and on the particular type of scleroderma. “For example, with diffuse variants of scleroderma, skin thickening develops rapidly in the first few years but then slows down, sometimes with noticeable skin improvement. It is not clear why this happens. But internally, damage can nevertheless continue,” Harris wrote.

“The key question is whether or not the internal organ damage reaches the point where it causes clinical problems,” he continued, mentioning a condition linked to scleroderma. “Pulmonary artery hypertension (PAH) is one of the most dangerous complications for patients with limited scleroderma. It turns out that if you monitor lung functioning in patients with limited scleroderma over time, it is common to see a gradual decline in some key laboratory measures of breathing function.” Lung function impairment, however, may not be sufficient for a diagnosis or even impact a person’s quality of life.

“Systemic scleroderma IS ‘systemic’ in that it does involve damage to internal organs. But, in many cases, the damage to an organ may never be serious enough to result in clinical symptoms” Harris concluded. “This is one of the reasons why your doctors monitor you closely with diagnostic tests. The goal is to identify any ‘functional’ internal problems early when it is easier to treat them.”