Subset of Immune B-Cells Linked to Vascular Damage in Some Patients, Study Suggests

Levels of a subtype of immune B-cells in the blood are increased in some people with scleroderma and associated with lower respiratory function, higher blood pressure in the lungs, and more kidney damage, a study reports.

The study, “CD21-low B cells in systemic sclerosis: A possible marker of vascular complications,” was published in the journal Clinical Immunology.

Scleroderma is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation and overproduction of collagen, a main component of connective tissue. This may cause the thickening and hardening of skin and internal organs.

Vascular complications — those relating to blood vessels — underlie several manifestations of scleroderma, and include sores of the fingers and toes, called digital ulcers, renal crisis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), or high blood pressure in the lungs. Renal crisis is a life-threatening complication characterized by an abrupt onset of high blood pressure and acute kidney failure.

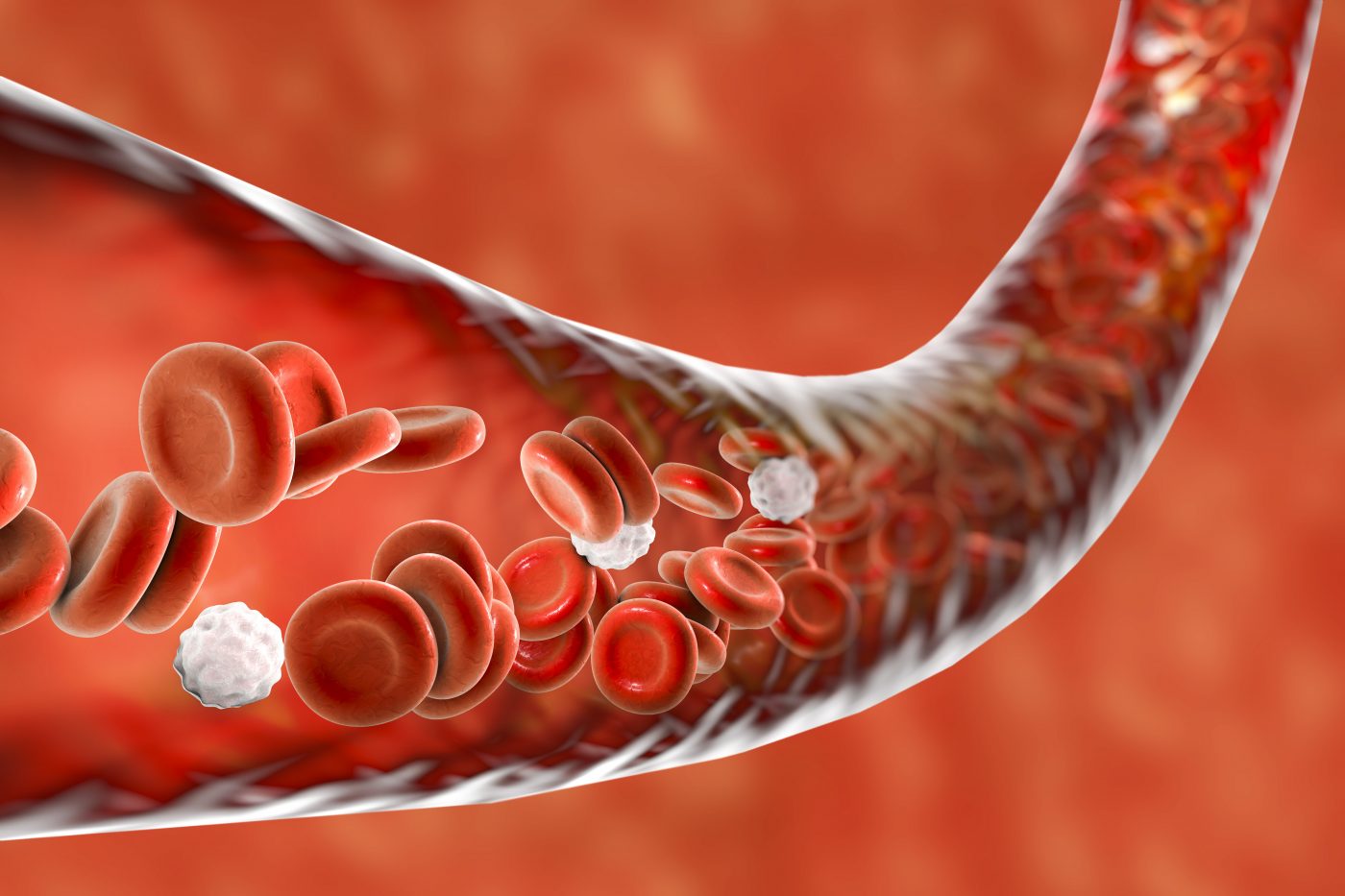

Both inflammation and vascular complications are influenced by B-cells, a part of the body’s adaptive immune system. B-cells play a critical role in autoimmune disorders by producing both antibodies that target the body’s own tissues, called autoantibodies, and signaling molecules called cytokines, which promote inflammation and fibrosis, or scarring.

A recent study found that B-cells with lower levels of a cell surface protein called CD21 were more prevalent in those with scleroderma. These cells, known as CD21-low cells and also described in people with systemic lupus erythematosus and other disorders, appear unreactive (anergic) to substances that would normally induce an immune response and are found in inflamed tissues.

This prompted researchers at Sapienza University in Rome to see whether the cells could be used to predict vascular complications in scleroderma.

The team analyzed 74 scleroderma patients — 40 with limited scleroderma and 34 with diffuse disease, mean age 54.5 — and 20 healthy people (controls).

Overall, the percentage of B-cells with reduced levels of CD21 was higher in people with scleroderma than in the healthy controls. Yet, only one third of the patients showed increased percentages of such CD21-low B cells, suggesting that these may represent a particular subtype of scleroderma cases, the researchers said.

These cells were more prone to a process called apoptosis, which refers to “programmed” cell death — as opposed to death caused by injury. Apoptosis, which involves the genetically determined elimination of cells, is a factor in many neurodegenerative diseases.

Greater proportions of CD21-low cells in people with scleroderma were associated with higher systolic pulmonary arterial pressure (sPAP), lower carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) — a measure of respiratory function — and lower levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is essential for the formation of blood vessels.

Those with more CD21-low cells had stiffer renal arteries, compared with the other participants. Renal arterial stiffness is predictive of kidney damage, which is known to occur in scleroderma cases.

“In addition to the alteration of B cell subpopulations, our results show a possible role of CD21low B cells in the pathogenesis [disease progression] of some vascular manifestations of the disease,” the scientists said.

No difference was noted between patients who developed digital ulcers and those who did not, suggesting that CD21-low B-cells might only operate on deeper, or visceral, tissue.

“We can assume that CD21low have a selective homing for internal organs. Further studies are needed to evaluate these assumptions,” the team added.