Black patients in US show ‘modest’ epigenic changes in immune cells

Study into life influences on genes notes need to include diverse groups

Written by |

Epigenetic changes in immune cells from African American women with systemic sclerosis (SSc) may differ from those in patients in of European ancestry, a study reported.

The finding “underscores the importance of research in patients with diverse clinical and sociodemographic characteristics, and of integrating genetic and social factors, to enable a thorough understanding” of epigenetics and other molecular processes that drive scleroderma, the researchers wrote.

They also noted that, although SSc “disproportionately affects women and African Americans,” Black patients are “dramatically underrepresented” in disease research.

The study, “Distinct genome-wide DNA methylation and gene expression signatures in classical monocytes from African American patients with systemic sclerosis,” was published in the journal Clinical Epigenetics.

Look at DNA methylation and gene expression in Black women

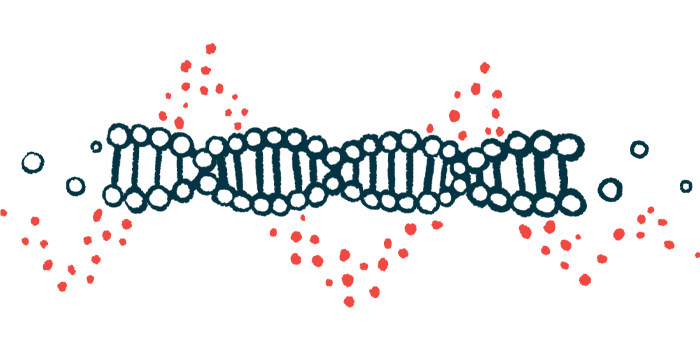

Epigenetics is the study of how lifestyle and environment affect a cell’s gene expression or activity — that is, which genes are turned on or turned off. Epigenetic changes are reversible, and they do not alter the actual DNA sequence.

Monocytes are a type of immune cell whose activity is known to be abnormal in people with scleroderma.

“The dysregulation of monocytes in patients with SSc is well established as evidenced by their increased numbers in both peripheral blood and in skin … and is associated with reduced survival,” the researchers wrote.

Prior research has associated epigenetic changes in monocytes with disease activity among scleroderma patients. However, previous research mostly included people of European descent — although the disease not only affects African Americans but also tends to be more severe in this population.

Scientists, at institutes primarily in South Carolina and Alabama, set out to characterize epigenetic changes in monocytes from African American women with scleroderma.

“Given the dysregulation of monocytes in SSc and the increased prevalence and severity of disease in African Americans, it is important to identify the mechanisms underlying this dysregulation and their potential contribution to the ethnic disparity,” the researchers wrote.

The team first analyzed methylation profiles in monocytes from 12 African American women with SSc and an equal number without the disease as controls. Methylation is a type of epigenetic change where a chemical motif called a methyl group is attached to the DNA molecule.

Differences in methylation profiles were “modest,” the researchers wrote. Out of more than 850,000 areas of methylation on the genome tested, only 19 (0.002%) showed significantly different levels of methylation between Black women with or without scleroderma. Findings indicated that most of these changes were in parts of the genome that do not contain protein-coding genes.

In a subsequent analysis, the scientists looked at gene expression profiles of monocytes from 16 African American women with SSc and 18 without the disease. Out of more than 25,000 gene transcripts analyzed, 1,272 (5%) showed significant differences in gene expression among the scleroderma patients.

Many of the genes found to be abnormally methylated or differentially expressed are involved in metabolic processes — the molecular mechanisms that the body uses to make energy and produce new molecules, the researchers noted.

“We show modest differences in DNA methylation and gene expression between patients and controls, and an enrichment of genes involved in metabolic processes,” they wrote.

Previous scleroderma research mostly in patients of European ancestry

The researchers noted that, while a few of the genes also have been implicated in prior scleroderma studies, these results show notable differences from work done mainly in people of European descent.

“Multiple analyses of gene expression patterns in different blood cell types from mostly European-derived populations consistently report a prominent upregulation of genes involved in immune and inflammatory processes in SSc patients.” This “contrasts with the weaker upregulation of inflammatory and immune genes we observed in classical monocytes from African American SSc patients,” they wrote.

Researchers cautioned, however, that a simple explanation based on race alone is unlikely to meaningfully account for these differences.

“Race is an imperfect proxy for social determinants of health such as racism and discrimination, economic stability, healthcare access and quality, education access, and environmental exposures. These social and environmental determinants are differentially experienced across groups and geography, resulting in health disparities,” they wrote.

“We postulate that these sociocultural factors experienced by our study participants are one of the reasons underlying our results,” the scientists added.

They also stressed that this study was small, so in a statistical sense its ability to detect meaningful associations was quite limited. Most of the patients were on immune-suppressing medications, which are known to affect methylation levels.

Additionally, the researchers noted that the study relied on participants self-reporting their race, without detailed information on their genetic ancestry.

“To mitigate against the limitations of this study it is essential that future studies genotype and includ[e] multiple African groups to fully capture African genetic diversity,” the scientists wrote.