Alternative Scleroderma Theory Advanced by 22 Years of Therapeutic Plasma Exchange

A case study, describing the successful treatment of a scleroderma patient with repeated therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) for more than 22 years, presents an alternative theory about the beneficial effects of the treatment and the disease itself.

The study “Successful long-term (22 Year) treatment of limited scleroderma using therapeutic plasma exchange: Is blood rheology the key?“ recently published in the journal Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation, advances the idea that scleroderma is linked to an abnormal clumping of red blood cells.

The report is linked to another interesting feature: The lead author of the study is also the patient himself, Edward Harris, a prominent figure in scleroderma society. Harris was diagnosed with scleroderma in 1990, and as Scleroderma News previously reported, gave up his career as the CEO of a software business to research his own disease.

Harris, who founded and funds the Scleroderma Education Project, already presented preliminary data from the case report last year at the 2015 American Association of Blood Banks Annual Meeting.

The report, crafted in collaboration with researchers from the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California; the University of Kansas Medical Center; and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, follows Harris’ journey and details observations made by the research team that support Harris’ disease mechanism theory.

When Harris started his TPE treatment in 1993, he suffered severe gastroesophageal reflux disease eroding his food pipe (oesophagus). He also experienced severe chronic chilling, Raynaud’s syndrome, and decreased lung function.

Although he did not have digital ulcers or other skin scleroderma symptoms, doctors noted that the capillaries on his fingers were enlarged. His symptoms did not respond well to medication, in fact they continued to get worse.

Since 1993 through current times, Harris has received TPE 16 times per year, in cycles of four treatments one week apart for one month, followed by two months off.

The study reports that after only one year of treatment, Harris’ Raynaud’s symptoms, consistent chilling, and reflux disease had improved significantly, and the damage to his oesophagus had healed. His lung function improved steadily, and in 2001 after eight years of treatment, lung function measurements showed that his lungs were as good as those of any healthy person his age.

In 1996, Harris and his physicians decided to stop the treatment to determine if continuous treatment was needed to control his condition — or if his three years of TPE had stopped the disease in its tracks.

Unfortunately, his reflux symptoms reappeared and six months later he resumed treatment. After several failed attempts, he successfully stopped using omeprazole for the reflux, attributing previous failed attempts to the abrupt discontinuation of the drug.

Except for mild Raynaud’s symptoms, for which Harris continues taking nifedipine, he is now free from scleroderma symptoms. Initial tests that showed increased antinuclear and anticentromere antibodies, typical features of scleroderma, are now totally normal.

Throughout the treatment, physicians noted another curious, standout observation: The rate at which Harris’ red blood cells sedimented (settled) when placed in a test tube decreased year after year.

Though Harris is not the only patient to receive TPE for scleroderma, and though the dominating theory for TPE is that the treatment removes factors such as autoantibodies, immune, or adhesion molecules, Harris is convinced that the key to his own treatment success lies in the abnormal behavior of his red blood cells.

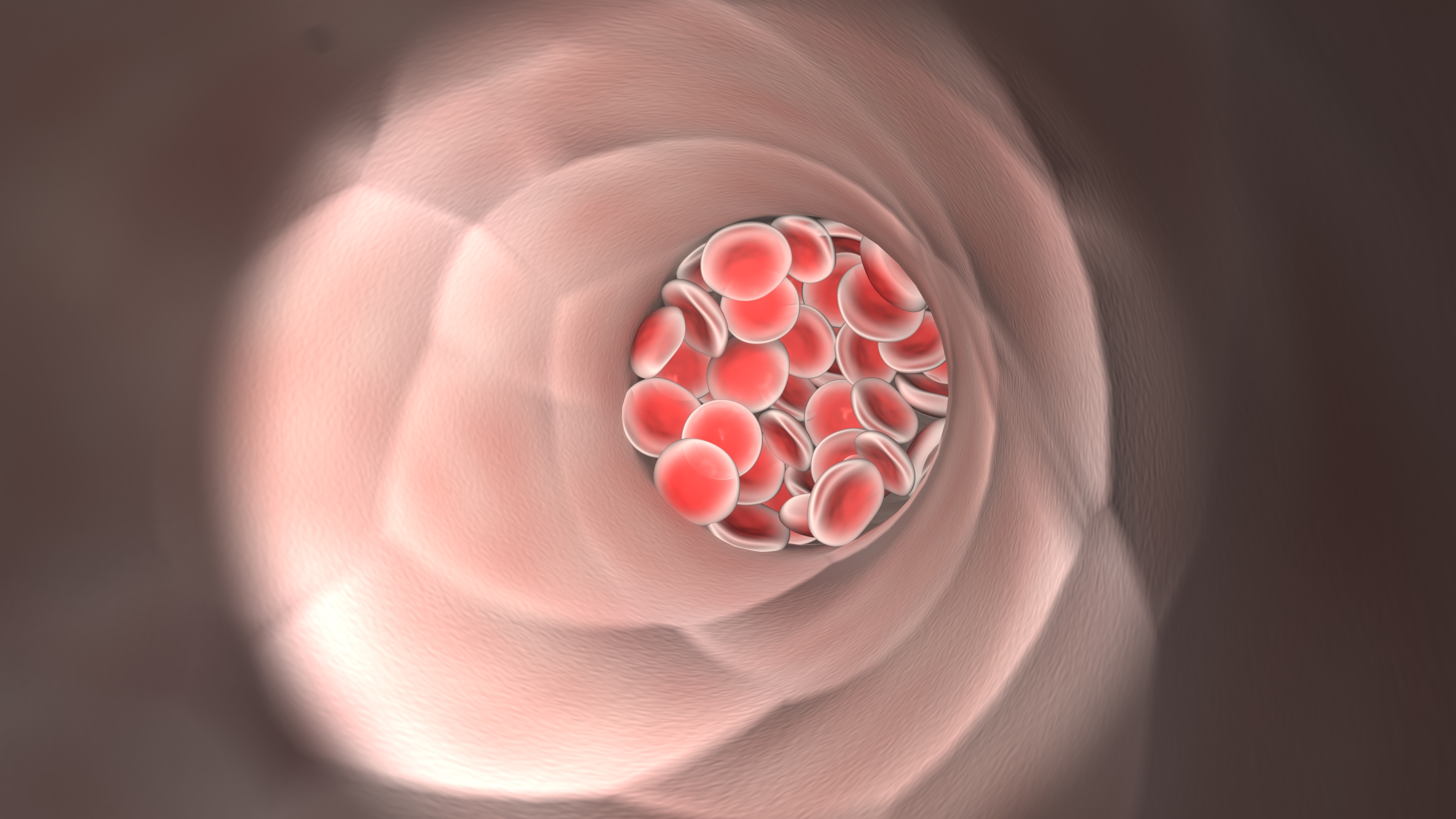

Based on observations that scleroderma patients have abnormally viscous (thick) blood, Harris and his team proposed a model of scleroderma resting on the idea that the clumping of red blood cells block microscopic blood vessels, leading to tissue damage and symptoms typical of scleroderma.

In May, Scleroderma News had the opportunity to interview Harris about the findings, after his presentation at the American Society for Apheresis (ASFA) 2016 Annual Meeting titled “Therapeutic Plasma Exchange for the Treatment of Systemic Scleroderma: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis.”

The presentation summarized and further analyzed previously published studies on TPE, showing that Raynaud’s and digital ulcers improved with the treatment, and that treatment additionally reduced blood viscosity.

Also at that time, Harris shared details about the TPE procedure, main findings of his research, and tips for other scleroderma patients.

Scleroderma News met Harris again to find out more about the scientific details behind the apparent success of TPE treatment.

The typical explanation for the therapeutic benefits seen with TPE is the reduction of blood circulating levels of possible harmful factors, such as autoantibodies. However, in your research article you suggest an alternative explanation based on abnormal blood rheology. Can you briefly explain why TPE treatments appear to benefit scleroderma patients?

A number of researchers have commented that the effects of a few TPE treatments last much longer than would be expected (commonly six months or longer after stopping a short course of TPE treatments) if all that TPE is doing is temporarily reducing the blood circulating levels of potential pathogenic factors such as antibodies. In conjunction with doing the literature review for the current paper, we also reviewed the research literature that showed that elevated blood viscosity (thickness/stickiness) occurs in the majority of scleroderma patients, primarily from red blood cell aggregation (clumping). Several of these studies also documented that elevated blood viscosity and RBC [red blood cell] aggregation is significantly reduced for a number of months following a single course of four weekly TPE treatments. Based on this, we hypothesized that the primary reason for the positive effects seen in TPE treatments may be from the reduction in red blood cell aggregation that occurs from mechanical separation of blood cells during the centrifugal cell separation process used during TPE.

Researchers have noted since 1979 that all scleroderma symptoms appear to develop starting from repeated trauma to the endothelial layer that lines the interior surface of blood vessels. This directly led to my proposing in 1993 that clumped red blood cells that are forced through capillaries that are small enough so they normally permit passage of one red blood cell at a time, may lead to the microvascular damage cited above, as well as potential microcapillary blockage if the clumps of red blood cells are large enough.

This new scleroderma pathogenesis model has major implications for the future development of new treatment approaches that do not require immunosuppression. Hypothetically, if the symptoms seen in scleroderma ultimately develop as a consequence of RBC aggregation, then any treatment that can disaggregate red blood cells and keep them disaggregated may prevent scleroderma-related symptoms from ever developing and potentially reversing some symptoms if systemic damage is not too severe. While TPE has been demonstrated to have RBC disaggregation effects in several research studies, there are several potential drugs that may also be able to accomplish this as well.

What additional research could be performed to support the finding that TPE is an effective treatment for patients with scleroderma, and that the hypothesis of RBC hyperaggregation is valid?

We have proposed a relatively simple initial clinical trial that can determine if TPE is an effective treatment for an initial subset of scleroderma patients and also help to separate out the relative contributions of: 1) temporary reduction of possible circulating pathogenic factors, and 2) mechanical disaggregation of red blood cells from the cell separation process used in TPE. The double blinded study would include two treatment groups plus a matched untreated control group. One treatment group would receive regular TPE treatments and the other treatment group would receive “autologous” TPE where the patient’s plasma is recirculated rather than replaced. In the autologous TPE group there would be no reduction in potential circulating pathogenic factors so any observed benefits would strictly be from RBC disaggregation.

We propose restricting the initial subject pool to anticentromere antibody positive limited scleroderma patients who have no major organ damage or other risk factors that would contraindicate TPE. Restricting the subject population to a slower-progressing variant of scleroderma with a single common antibody type will create a “best-case” study. If TPE is not effective in this population, it would be very unlikely to work in more rapidly progressing diffuse variants of scleroderma.

Based on feedback you received after the presentation of the findings at ASFA 2016 and their recent publication, how do you feel the medical and scientific community is reacting to TPE as a promising therapy?

It is still very early in our efforts to educate the scleroderma community about both TPE as a potential treatment option and the more important issue of understanding the role of blood hyperviscosity in the development of scleroderma symptoms. Our case report abstract was initially published in the research journal Transfusion and the full case report was just published in Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation. The abstract version of the TPE review poster that I just presented at the ASFA conference was published in the Journal of Clinical Apheresis. While all of these are well-respected journals, they are not normally read by rheumatologists.

Many physicians who are not very familiar with TPE (this includes most rheumatologists) have a lot of misconceptions about TPE, including concerns about safety and venous access. These concerns are not supported in the extensive research literature on TPE. TPE is considered to be a very safe procedure overall and most patients can receive long-term TPE with normal peripheral venous access. The vast majority of TPE adverse events are very minor (e.g., hypotension or citrate reactions) and are easily dealt with during the TPE process. There are rare allergic reactions, some of which can be serious, which is why TPE should always be done by an experienced staff in a setting that is able to deal with any serious complications.

Overall, we are finding that as physicians hear about TPE and the research on scleroderma blood hyperviscosity (often from patients who follow our research through scleroderma-focused patient support groups or the Scleroderma Education Project website), they are increasingly open to learning more about this research. Most physicians (appropriately) remain skeptical at this point but at least a few physicians that have learned more about TPE have indicated that they are willing to consider trying TPE as a treatment option according to a number of patients that I have been in contact with since our initial research has been published.

What is the next step or future goals for you and your team concerning research on TPE?

Our recent and currently active research and writing projects include:

- The submission of an abstract to the American College of Rheumatology meeting to be held in Washington, DC. The focus of the abstract is a review of the research literature on how TPE treatments effect Raynaud’s and digital ulcer symptoms in patients with systemic scleroderma.

- We are working with several patients who are actively considering trying TPE with the support of their physicians. Upon request, we have prepared a document that suggests standardized guidelines for an initial one-year trial of TPE. The purpose of these guidelines is to foster the use of a standardized protocol for administering TPE along with suggested testing before, during, and after the TPE trial. If physicians follow these guidelines, this will greatly facilitate data gathering and analysis that will help shape a proposed full clinical trial of TPE. The TPE Guidelines document is available by contacting me at [email protected] and will also be available on the Scleroderma Education Project website (SclerodermaInfo.org) in the near future.

- Following the poster presentation of our review article titled “Therapeutic Plasma Exchange for the Treatment of Systemic Scleroderma: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis” at the ASFA conference this May, I approached a number of rheumatology journals to gauge their interest in this topic. I was very pleased that two top rheumatology journals plus the new research journal focused on scleroderma have all expressed interest in reviewing the manuscript when it is completed this Fall. This suggests that the senior editors of these research journals believe that the topic of using TPE to treat scleroderma will be of interest to the scleroderma research and clinical community.

- As a companion piece to the new TPE Guidelines document mentioned above, I am co-authoring (along with an infusion nurse who has more than 25 years of experience administering TPE) a patient-focused article titled “Therapeutic Plasma Exchange: A Guide for Newbies“. This document is intended to provide practical tips for anyone about to start TPE treatments (for any reason, not just scleroderma) that should make the experience more likely to be successful and also make the experience of receiving TPE treatments more comfortable.

- We are in the process of conducting some follow-on research directly related to our recently published case report. At the time TPE was initiated with this patient in 1993, it was not possible to easily measure whole blood viscosity (WBV) in order to directly determine if the TPE treatments temporarily reduce blood viscosity, as we had hypothesized would occur following each round of TPE treatments. Through the generous support of a company called RheoVector, which makes and sells modern equipment to measure whole blood viscosity and also provides WBV testing for researchers, we have started to directly monitor WBV before and after each TPE treatment round in the patient described in our case report. While we have not yet confirmed this with a second round of testing, our initial results were exactly in line with our predictions: the patient’s WBV was elevated before TPE treatments and significantly reduced following a round of four weekly TPE treatments.

For those interested in a copy of the Clinical Hemorheology and Microcirculation‘s manuscript (allowed under copyright restrictions), or a copy of an extended version of the poster presented at ASFA, both documents can be freely downloaded from the Scleroderma Education Project website: CHM Case Report Manuscript, ASFA Conference Extended Handout.